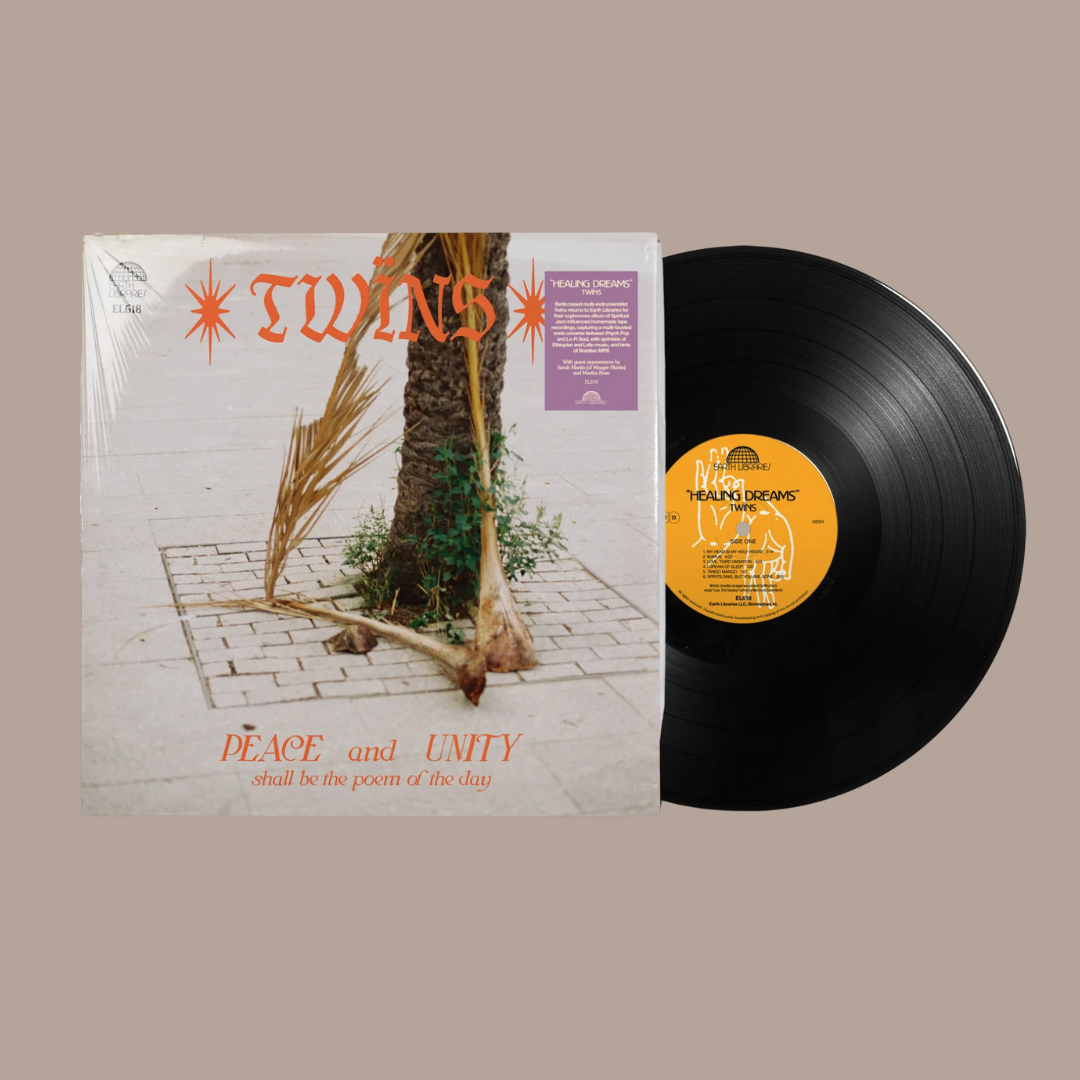

TWÏNS - Healing Dreams - Banyan Green Recycled

TWÏNS - Healing Dreams - Banyan Green RecycledTWÏNS - Healing Dreams - Banyan Green Recycled

Regular price $26.00Unit price per

TWÏNS

Following their 2022 debut album “The Human Jazz”, Berlin based artist Twïns returns to Earth Libraries with “Healing Dreams”, their second LP. After exploring the nature of loss and grief in their first record, this album represents the spiritual journey that follows, one towards healing and growth, both as an individual and as a community.

The recording studio can be a magical place to work in – many stories have been told about such legendary spaces like Abbey Road, Hitsville U.S.A., or the Van Gelder Studio. Also the home recording studio can be a place where magic happens. Think of Lennon’s Tittenhurst Park or Can’s Inner Space.

Miro Denck, the multi-instrumentalist and visual artist behind Twïns chooses to record their uniquely vintage and tapey creations in their bedroom while aiming for sonic escapism, combining a committed DIY aesthetic with a strong nod to the sun-kissed studio recordings of the ‘70s that inspire their work.

“Healing Dreams” transports the listener into a multi-faceted tropical universe that feels a long way away from Berlin. It is warm and mellow, with floating questions that are explored in soft contemplation by the sea in the bossa-tinted “Marisma”, or in the depths of the meditative mind, in the free-form improvisation “Introspection”. A sense of personal pain and melancholy can be felt in some of the lyrics, which continue to turn over the complications of relationships in all their forms, but the sunbeams rarely vanish.

The influence of spiritual jazz is clearly present in Twïns’ work, accompanied by a humble and joyous exploration of their most treasured aural aesthetics from the ‘70s. The soft rock of Paul McCartney and George Harrison inspire a gentle tone, in which Twïns shares their rejection of violence and aggression in the increasingly dark world that we inhabit. The words: “Peace and unity shall be the poem of the day” are written on the front cover of the LP, transcribed from the real dream that inspired the album’s title.

Infusions of Ethiopian sounds can be found alongside hints of gospel and deep soul. There is some explorations of Brazilian MPB, and an omnipresent Latin flavour crystalized in “Oriente”, a cover of a Henry Fiol song originally composed by Cheo Marquetti. Detailed research and deep knowledge of the music that inspired this record is a crucial part of its process and sound, and Twïns remains beautifully dedicated to this self-imposed structure.

Community spirit was integral in the making of “Healing Dreams”, distinguishing it from the more solitary space of Twïns’ first record. The album was written and recorded simultaneously, with each idea slowly explored and developed as it emerged. There were creative contributions from numerous Berlin contemporaries, a multinational group including vocalist Sarah Martin from Meagre Martin, percussionist Ale Borea, tenor saxophonist Gustavo Obligado, alto saxophonist Simon Herody, vocalist Trinidad Doherty, pianist Wojtek Swieca, cellist Cristobal Pinto, drummer Tom Dayan, and flautist and singer Martha Rose.

“Healing Dreams” is out May 23, 2025 on Earth Libraries.